Composing systems out of smaller microservices has been commonplace for several years now. One trade off is increased complexity around development environments.

Suppose the system you are working on consists of hundreds of services that all potentially make requests to one and other. If you are unlucky you might be faced with the task of spinning everything up locally or within a new cloud provider account.

This is costly and often too much work. You might be inclined to blindly deploy to a test or staging environment, after testing your service runs as expected in isolation. Even then, there is a high probability of breaking things for other users. You are also likely to suffer a slow feedback loop with every single change requiring a build and deployment.

An alternative idea is to patch in a new implementation from a local environment into a real test environment that is already running all of the other services. This could be a full or partial replacement. You could just patch in or overlay a new implementation of an existing resource, with all other requests going to the existing implementation.

A contrived scenario

Imagine that we have a service with the resource /message that returns Hello world!!!. It also provides the subresources /message/lower and /message/upper which return lower and uppercase representations of the same string.

$ curl https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message

Hello world!!!

$ curl https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message/lower

hello world!!!

$ curl https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message/upper

HELLO WORLD!!!

Unfortunately, as our former selves had a shameful past of being microservice astronauts, the case transformation happens in another service instead of being a local function call. To make matters worse, the transformation service cannot be recompiled for Linux as the code was lost in a fire. The team that owns it have warned us that it incorrectly interprets certain extended characters and that a correct implementation would actually cause huge problems to other services that have worked around it. Let’s let sleeping dogs lie.

Anyway, our stakeholders have decided that three exclamations after Hello world is excessive and a waste of bandwidth, so we have been tasked to create a new version of the service with only one.

Before deploying, we want to preview the change running locally by having it appear in a remote test environment. This provides an opportunity to test its interaction with other services.

A solution with Consul and Envoy

One way to do this is with a service mesh. This is a way of connecting services together to build a secure, observable and malleable system. HashiCorp introduces the concepts more fully in this video. Consul and Envoy Proxy are used to form this example service mesh.

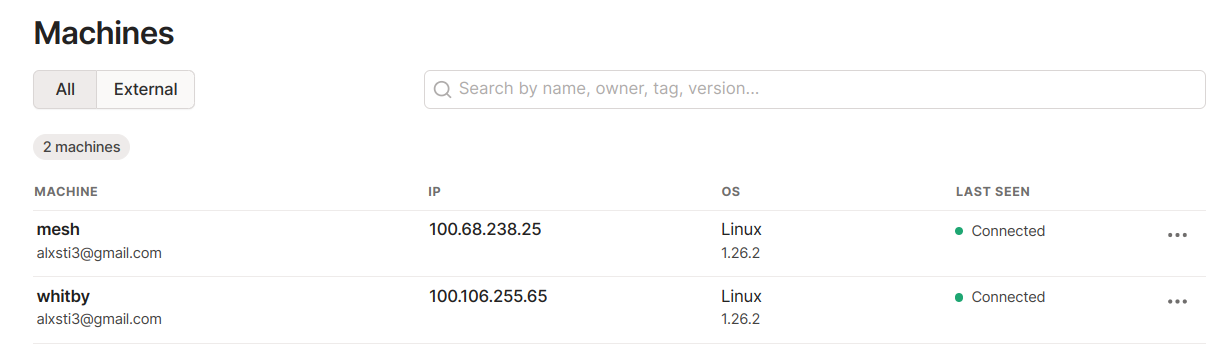

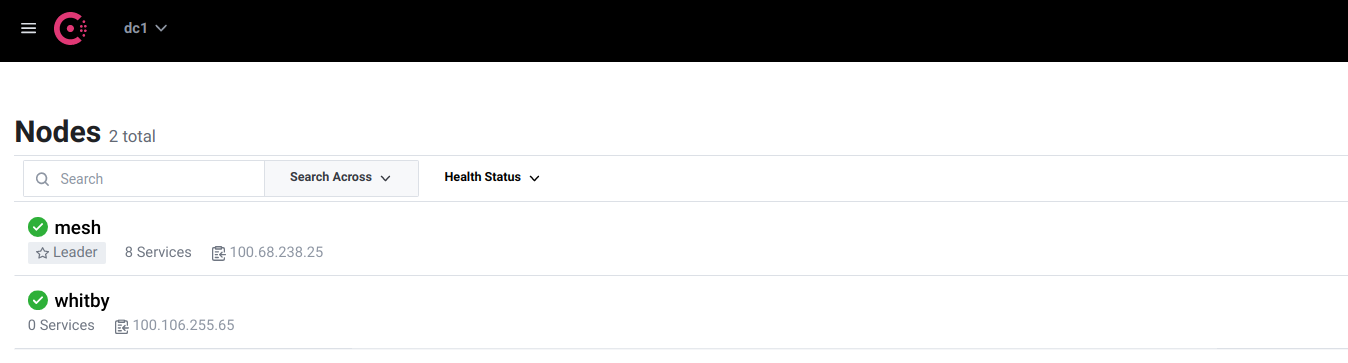

The test environment is running within a cloud provider. My local development machine, whitby joins the same network, thanks to Tailscale.

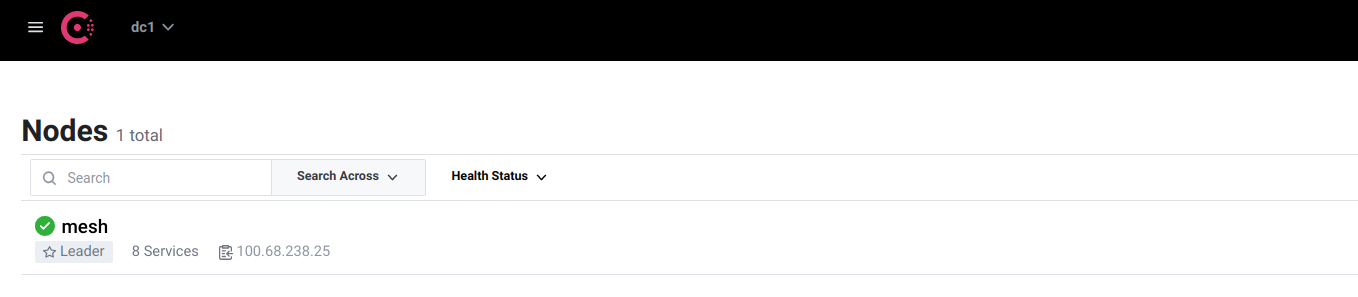

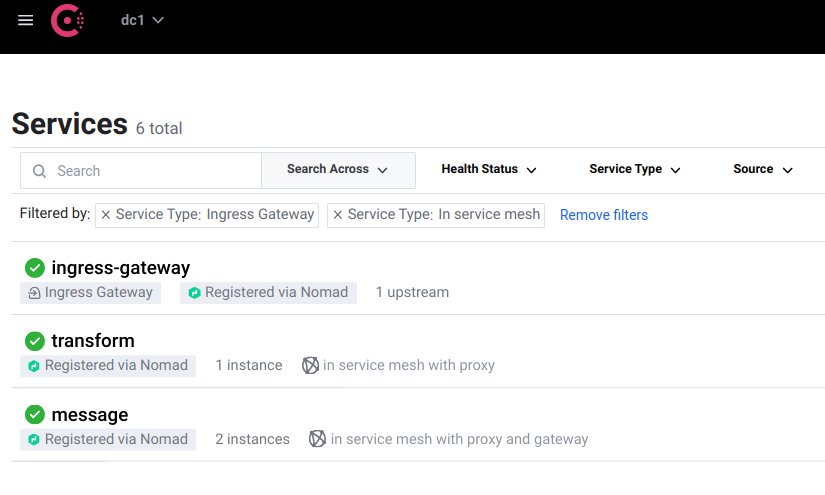

We can see the test environment has a single node in Consul where all of the services are running.

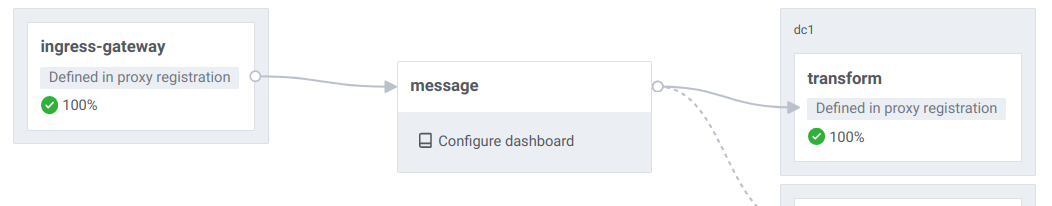

For this example scenario, we are running services called message and transform. message makes calls to the transform service.

Services within the mesh are accessed from the outside via an ingress gateway also shown here. This is where the above curl commands are issued. It is the entry point into the environment. The ingress gateway is configured to accept ingress into the message service, but not transform. Requests to transform can only originate within the mesh.

The test environment uses Nomad to schedule the services running as Docker containers but they could be running on AWS ECS, Kubernetes, VMs… or a development machine, as we will soon see.

To patch in to the test environment, I start a Consul agent on my local machine, ensuring the Tailscale IP is used and enabling gRPC, which is how the Envoy retrieves its configuration on an on-going basis.

$ consul agent -retry-join mesh...tailscale.net \

--advertise $(tailscale ip -4) \

--data-dir /tmp/consul \

-hcl 'ports { grpc = 8502 }'

The agent appears in Consul.

Note that Consul’s LAN gossip protocol, as its name would imply, is not designed to run across the Internet. Running a local agent is a bad idea and a fix for this is described later on.

Our service under development is the message service, which needs to be registered the local Consul agent. The configuration is largely the same as a deployed version of the service, only with different metadata. This is important as it means that we can isolate this instance of the service later on.

The configuration also references the transform service. As the transform service is within the mesh with no external ingress configured, a non-mesh client cannot just connect to it directly as mTLS is used between services.

service {

id = "ajr-local-fix"

name = "message"

port = 5001

meta {

version = "local"

}

connect {

sidecar_service {

proxy {

upstreams {

destination_name = "transform"

local_bind_port = 4001

}

}

}

}

}

$ consul services register message-service.hcl

Registered service: message

To receive traffic, Envoy is started. Consul configures it for us. All we need to do is specify the service ID we just registered.

$ consul connect envoy -sidecar-for ajr-local-fix

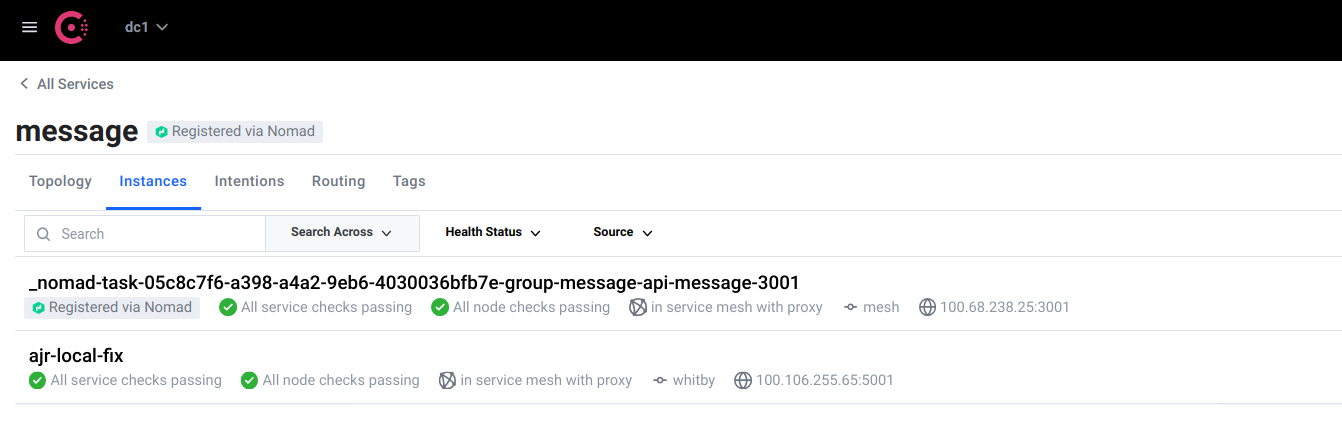

The service appears in Consul as a new instance alongside the real deployed instance.

Finally, the service itself is started.

$ PORT=5001 MESSAGE="Hello world!" TRANSFORM_SERVICE_URL=http://localhost:4001 \

./routing-demo

Note the TRANSFORM_SERVICE_URL environment variable. By calling the transform service through Envoy, the message service can just do a dumb HTTP call, offloading any security (mTLS, access control) considerations.

We get traffic to both the deployed and locally running service.

$ curl https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message # local

Hello world!

$ curl https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message # live

Hello world!!!

$ curl https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message/upper # local

HELLO WORLD!

L7 configuration entries to the rescue

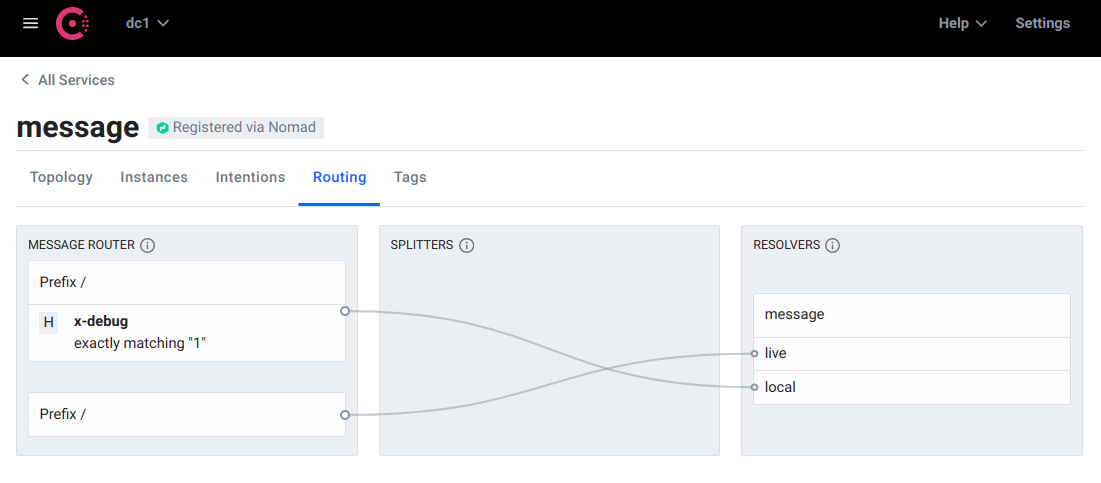

This is a good start, but both service instances are receiving requests in a round robin. We need to guard the local version so that it only receives traffic when a certain condition is met, such as an HTTP header being present and containing a certain value. This can be achieved with a service resolver and service router.

Firstly, we define the resolver which uses service metadata to form subsets of the service instances. Using metadata specified when the service is registered in Consul, the sets can be defined with an expression.

Kind = "service-resolver"

Name = "message"

DefaultSubset = "live"

Subsets {

live {

Filter = "Service.Meta.version == v1"

}

local {

Filter = "Service.Meta.version == local"

}

}

Routing by a header

A router allows us to direct traffic to those subsets with some simple rules. Note that if none of the rules defined below match, the default subset, live is used.

It is possible to route to the local subset if a header is set.

Kind = "service-router"

Name = "message"

Routes = [

{

Match {

HTTP {

Header = [

{

Name = "x-debug"

Exact = "1"

}

]

}

}

Destination {

ServiceSubset = "local"

}

}

]

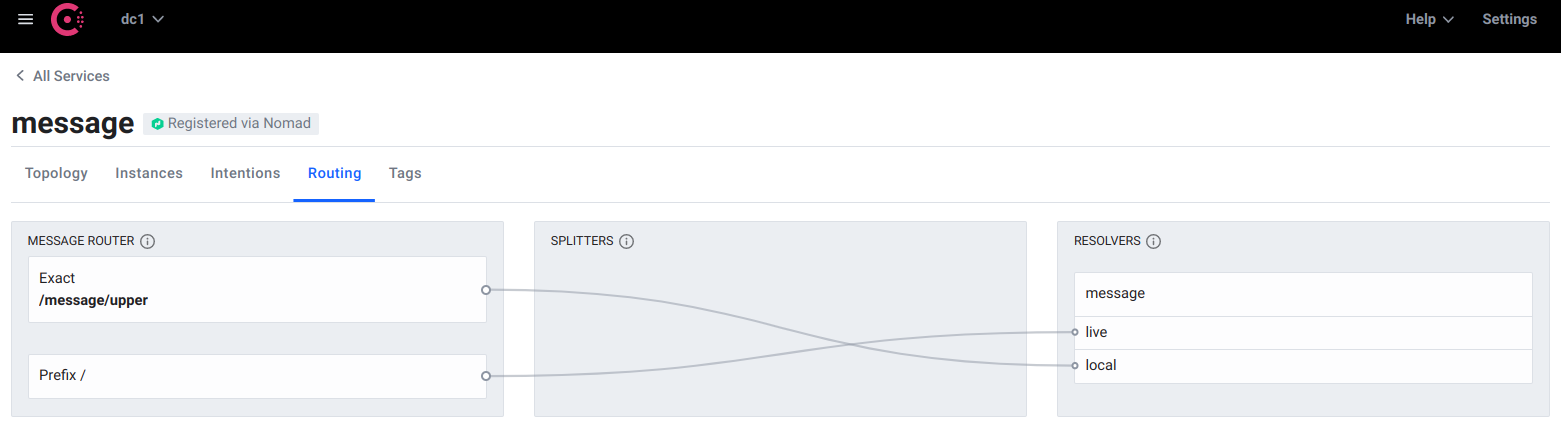

Applying these entries causes the routing logic to be reflected within a few seconds.

$ consul config write resolver.hcl

Config entry written: service-resolver/message

$ consul config write router.hcl

Config entry written: service-router/message

$ curl -H "x-debug: 1" https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message # local

Hello world!

$ curl https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message # live

Hello world!!!

The output from the local message service instance can be changed by restarting the process with a different environment variable. The change is immediately available all other services running in this environment that know to pass the x-debug: 1 header. If the services are set to propagate context or in other words, pass that header on to any services that they call, end to end tests can be run that exercise the local service.

$ PORT=5001 MESSAGE="Local hello world" TRANSFORM_SERVICE_URL=http://localhost:4001 \

./routing-demo

$ curl -H "x-debug: 1" https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message/upper

LOCAL HELLO WORLD

There was no need for a redeploy, just a restart of the process.

Routing an entire resource

Instead of looking for the x-debug header, we could specify that requests made to the /message/upper subresource are sent to the new implementation. This is a minor change to the service router.

Kind = "service-router"

Name = "message"

Routes = [

{

Match {

HTTP {

PathExact = "/message/upper"

}

}

Destination {

ServiceSubset = "local"

}

}

]

The routing rules can be changed without restarting or redeploying. The change takes effect immediately.

$ curl https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message

Hello world!!!

$ curl https://some-service.test-env-1.mycompany.com/message/upper

LOCAL HELLO WORLD

This is a great example of using resolvers and routers to to patch a service at the resource level. We can apply the strangler pattern to older services, by gradually overriding resources and pointing them to a new implementation, while sending everything else to the old implementation.

The same mechanics can be applied to a blue-green or canary deploy, where traffic is routed between different deployed versions of a service. This arrangement could be for a few minutes during a deployment, or for several months as part of a longer running migration project.

LAN gossip and slow networks

Consul agents are designed to run in close proximity on the same low latency network. This is clearly not the case if an engineer is working from home or a train.

Remote Consul agent

An alternative approach is to provision a remote Consul agent.

For this to work, a minor adjustment is made to the service registration.

service {

id = "ajr-local-fix"

name = "message"

port = 5001

# use service instance IP, not that of the remote Consul agent

address = "whitby...tailscale.net"

meta {

version = "local"

}

connect {

sidecar_service {

proxy {

# also set here for checks to pass

local_service_address = "whitby...tailscale.net"

upstreams {

destination_name = "transform"

local_bind_port = 4001

}

}

}

}

}

Starting Consul is almost the same. We need to tell Envoy to connect to the remote Consul agent.

$ consul connect envoy -sidecar-for ajr-local-fix \

-grpc-addr remote-consul-patch-in...tailscale.net:8502

To abstract things, a tool that provisions patch in agents on demand (perhaps on something like AWS Fargate or very small VM) with associated configuration would be straightforward to implement. This could make patching in a very simple process. It might look like this:

$ patch-in -env test-1 -service message -port 5001

Provisioning a remote dev Consul agent... done!

Registering service: message with ID local_message_d4ce479a-5bb2-4a2c-a802-ef1ee47d0465

Starting local Envoy proxy.

Ready to go. Please start your local service on port 5001.

Make your local environment remote

The latency problem also goes away if what we have been calling the local environment was on a remote VM on the same network as the rest of the Consul agents. Remote development is a very interesting topic.

Conclusion

In the example scenario we have:

- started a local version of the service

- patched it into a real test environment

- seen requests to the environment be routed to the local service as dictated by matching rules

- seen the local service call out to the transformation service through the service mesh

- seen how the local service can be called by other mesh services to test integrations

- made changes to the local service and seen the changes immediately without redeploying

What particularly impressed me was the tight inner feedback loop. I was able to patch a local implementation of the message service into a real environment and make changes to it without redeploying. I could potentially attach a debugger or REPL to the running process for even more insight into the running of my development service.

Astute readers will have noticed I have not mentioned security, namely ACLs and certificates. These are an essential ingredient to ensuring that only trusted services can join the mesh.

It is likely that this approach is only appropriate for test environments. It would be a bad idea to attempt with a production environment, unless you have a clickbait blog post cued up: I accidentally put my laptop into production and here’s what happened!

Tooling to automate and secure the patch in process would be essential. This needs to just work for engineers and not get in their way. The whole point of this exercise is to make things easier.

Some might say that the importance of running locally is being overstated and that the traffic management features of Consul are the real killer feature here. Deploying a branch to a test environment and just patching that in might actually be good enough. I’d love to know what you think.

Comments and corrections are also welcome. I’m @alexjreid on Twitter.

Update: prior art

It turns out that this is not a new idea. Ambassador Telepresence sums up what I have been trying to say far better in their documentation:

A good way to meet the goals of faster feedback, possibilities for collaboration, and scale in a realistic production environment is the “single service local, all other remote” environment. Developing in a fully remote environment offers some benefits, but for developers, it offers the slowest possible feedback loop. With local development in a remote environment, the developer retains considerable control while using tools like Telepresence to facilitate fast feedback, debugging and collaboration.

Links

- Consul L7 Traffic Management describes service resolvers, routers and splitters in more detail.

- Teleprescence from Ambassador is a similar idea if you’re on Kubernetes

- Image credit: photo by John Barkiple on Unsplash