DynamoDB is often a perfect fit as the primary, operational system of record store for many types of application. It is fast, maintenance free and (if you use it well) economical. However it cannot perform aggregations or provide analytics on the data it holds.

Reflecting the same data in another store like Apache Druid is commonplace. The below video demonstrates this idea in operation. The DynamoDB system of record is updated and Apache Druid is then used to perform aggregations on up to date values. This post will delve into some of the details about how it all works. The code running is available in this repo.

Events not mutations

Apache Druid can ingest and store huge, huge volumes of events for interactive analysis.

Events are things that have happened at an exact point in time: a user buys something, a temperature reading changes, a delivery van moved and so on. It is useful to be able to aggregate these events interactively to spot trends and understand behaviour. Events can be filtered and split based on dimension values, allowing us to explore data. In addition, flexible data sources provide engineers with an easy way of gathering metrics to surface to end users. You have tweeted in 93 times today!

Harvesting events from systems that do not already emit events can be something of a challenge. Updating a single record does not easily align with how Druid works. Druid stores data in segments that are immutable. The segment in which an event is stored is determined largely by when the event happened. The only way to change or remove a single event is to rebuild the segment without it.

If we can tolerate data only updating once a day, a batch job could drop and replace large time intervals. By casting the net wide, we will hopefully reflect any updates from the operational store, albeit in the most inefficient way possible.

It also becomes a challenge knowing where to place the records, as pseudo events, in time. If a user signed up in 2015, does their record always live in the 2015 segment? Or does the user cease to exist in 2015, and jump forward to a 2022 segment? If it doesn’t, that implies we will have to reingest the last seven years’ worth of data. This just doesn’t feel right.

Change data capture to the rescue

Luckily, many operational databases support change data capture streams. This provides transactional events whenever changes are written to a database table. Rather than conveying a business fact, they simply state that a change has occurred within the table. For instance:

record in user table with key 42 updated at 10:53AM! here’s the old version and here’s the new version.

Magic Druid events

A change event contains the time, type of database operation (insert, modify, delete) and importantly both the old and new images of the item being changed. With a little bit of processing, these events can tailored for Druid.

Two additional fields need to be computed, retraction and count.

Retraction

A new record is an addition so retraction: false.

A modification to an existing record is both a retraction of previously asserted record as well as an addition of the new, replacement record from that point in time onwards. Two events would be stored in Druid: one with the old values with retraction: true and one with the new values and retraction: false. Both events would take their event time from the change event.

When modifying a record, a retraction only needs to be emitted if a known dimension has changed. Other changes can be disregarded. This can be deduced by comparing the dimension values in both the old and new images.

;; Emit a retraction and an assertion if dims have different values

;; oldImage and newImage will have come from the change stream!

(let [dims [:location :language :customer_id]

old-image {:location "UK" :language "en" :customer_id "42"}

new-image {:location "US" :language "en" :customer_id "42"}]

(when-not (= old-image new-image))

(do

;; druid-event merges image with the second map, setting :count to

;; -1 if a retraction, otherwise 1

(druid-event old-image {:timestamp t :retraction true})

(druid-event new-image {:timestamp t :retraction false}))))

; => {:location UK, :language en, :customer_id 42, :count -1, :retraction true, :timestamp ...}

; => {:location US, :language en, :customer_id 42, :count 1, :retraction false, :timestamp ...}

Finally, if the record is being deleted then previously asserted events need to be retracted from that point onwards, so retraction: true.

Historical values are not deleted. The record will be counted until the time of the retraction. Storing events in this way allows Druid to run temporal queries, as of a certain date interval. This is achieved by adding __time to the WHERE clause in Druid SQL, or by specifying an narrower interval in a native Druid query.

This allows the data source to answer questions like what was the count for this customer during July 2022?

Although it may be beneficial to include this value in the event stream for debugging purposes, it is not always necessary to ingest it into Druid. The change is conveyed using the count value, discussed in the next section.

Count

A retracted event has a count value of -1. A non-retracted event has a count value of 1.

Conceptually similar to a bank account, reducing the positive and negative count values with an addition will give us the current count balance.

The below vector represents five additions.

(reduce + [1 1 1 1 1]) => 5

If a retraction happens later, this is appended to the additions. The same reduction will see the count will decrease.

(reduce + [1 1 1 1 1 -1]) => 4

The equivalent Druid SQL is SELECT SUM("count") FROM datasource. A WHERE clause could be added to filter by any defined dimension. This could be used to only show the count relating to a given customer, as well as the collective value. Other Druid queries are of course possible, for instance splitting by dimensions such as country and only showing the topN dimensions.

Rollup

Storage and compute costs will rise with a large number of events. This is similar to snapshots sometimes found in event sourced systems. Rather than replaying every event, the reduction starts with an opening balance as the initial value of the sum.

The first element in the vector below is the opening balance of 292. Subsequent values are applied to it.

(reduce + [292 1 1 1 1 -1]) => 295

Storage and compute time can be reduced by rolling up when the events are ingested. If the use case can tolerate granularity of a day, Druid can be told simply store the reduced value for a given set of dimension values for a particular day.

Assuming the six events from the previous section [1 1 1 1 1 -1] were the only events for that day, Druid would store a count of 4 in a single pre-aggregated event. It now has less work to do at query time. For rollup to work, all dimensions should be low cardinality.

Sometimes a reduction will yield a 0 which is a noop.

(reduce + [1 -1 1 -1 1 -1]) => 0

The frequency at which this occurs depends on how the table is used. For instance if a record is consistently created with a pending state and soon after always transitions to an active state, a count of 0 will be stored for the pending state once for each hour for each unique set of dimensions. If the query granularity was finer, this situation might be even worse. It is mostly harmless, but it is a waste of space. Good news though, Druid makes it trivial to filter out during (re)ingestion. Alternatively, the state dimension could be dropped but this would prevent filtering and grouping on a potentially useful dimension.

Subsequent batch jobs may also roll up older data further.

As all dimension values need to be the same in order for a set of events to be rolled up, including a high cardinality dimension such as a unique identifier like

order_idwill hinder the effectiveness of this feature, perhaps even stopping it from having any effect whatsoever.

DynamoDB

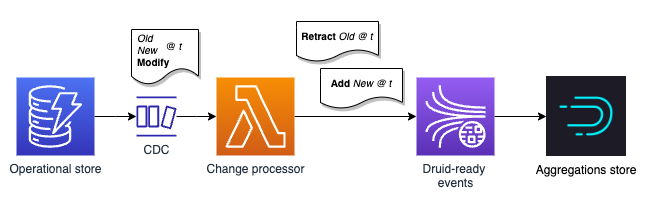

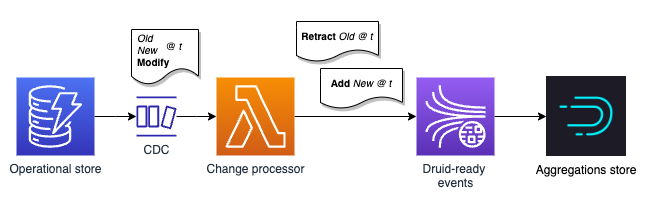

This approach can be used with DynamoDB as shown in the simple architecture below. The requirement is to provide a flexible data source that can provide a count which can be split and filtered by a number of dimensions. For instance: location with the most users, most active user today and so on.

The operational store is configured with a DynamoDB stream that triggers a Lambda function when items are added, modified or deleted. The Lambda function transforms the change events into the Druid events described previously.

The Druid events can be written to a Kinesis stream or Kafka topic which is consumed by Druid. Changes are reflected within a few seconds. The realtime ingestion rolls up the events by the hour and a later batch job rolls up to a day.

Change Lambda handler

The interesting part of an example Lambda handler is shown below. The complete code is available in this repo. You could implement this in any language and run it outside of AWS Lambda if you prefer.

(defn process-change-event

"Processes a single change event record from DynamoDB"

[event]

(let [t (get-in event [:dynamodb :ApproximateCreationDateTime])

event-name (:eventName event)

dims [:rating :country]

;; select-keys-s is the same as select-keys just extracts the value from a

;; DynamoDB string i.e. {:key {:S "value"}} => {:key "value"}

old-image (select-keys-s (get-in event [:dynamodb :OldImage]) dims)

new-image (select-keys-s (get-in event [:dynamodb :NewImage]) dims)]

(case event-name

"INSERT"

[(druid-event new-image {:timestamp t :retraction false})]

"MODIFY"

(when-not (= old-image new-image)

[(druid-event old-image {:timestamp t :retraction true})

(druid-event new-image {:timestamp t :retraction false})])

"REMOVE"

[(druid-event old-image {:timestamp t :retraction true})])))

(defn process-change-events

"Processes a sequence of change event records. Lambda entrypoint."

[lambda-event]

(let [druid-events (mapcat process-change-event (:Records lambda-event))]

;; send druid-events to an output Kinesis stream, Kafka topic, etc.

(clojure.pprint/pprint druid-events)))

Conclusion

The approach was tested by ingesting around twelve million synthetic events with a single data node Druid cluster

running on an r6gd.xlarge instance. Storage footprint was around 350MB including five string dimensions. Query performance is consistently in low double digit milliseconds without cache. Example code is available in this repo.

This very simple pattern provides a flexible, high performance data source that allows counts to be split and filtered by the included dimensions. As Druid’s segments are immutable and stored on S3, additional historical nodes can be added trivially in order to scale reads. The only code required is that of the Lambda function to convert CDC events into Druid events.

But just how flexible do you really need to be? The data source is immensely flexible but maybe you don’t need it. You can certainly aggregate in simpler technologies than Druid! It may be acceptable to simply accumulate the values in a Lambda function and store the values in DynamoDB.

If it feels like you are starting to write your own poor man’s Druid or you already happen to have a Druid cluster available, then this approach may be worthy of consideration… particularly if your use case can benefit from the temporal capabilities shown or you are planning on building a user-facing analytics application.

Credit

Of course this is not that novel. Double entry book keeping has been around for a while.

Imply have recently published this great post which overlaps with this one. I wish I had read it before writing this!

Many of the concepts are also found in event sourcing. Assertions and retractions are found in Datomic.

Datomic is indelible and chronological. Information accumulates over time, and change is represented by accumulating the new, not by modifying or removing the old. For example, “removing” occurs not by taking something away, but by adding a retraction.